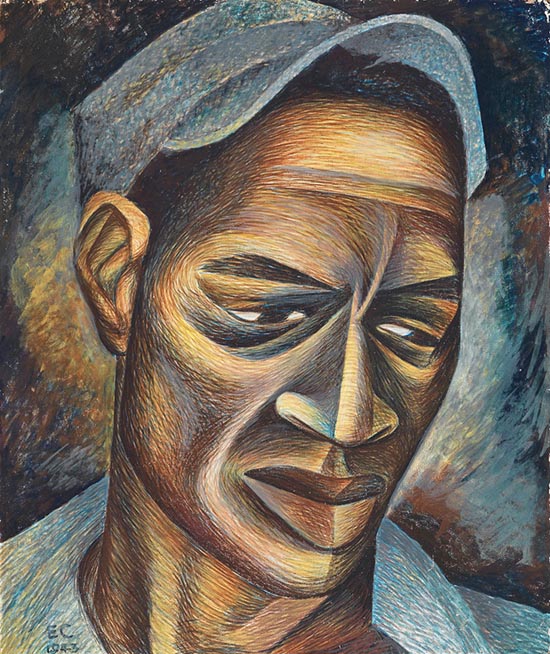

“I have always wanted my art to service my people — to reflect us, to relate to us, to stimulate us, to make us aware of our potential.”*

Elizabeth Catlett (1915-2012) was an African American Mexican artist and activist who resided in Mexico for over sixty years.

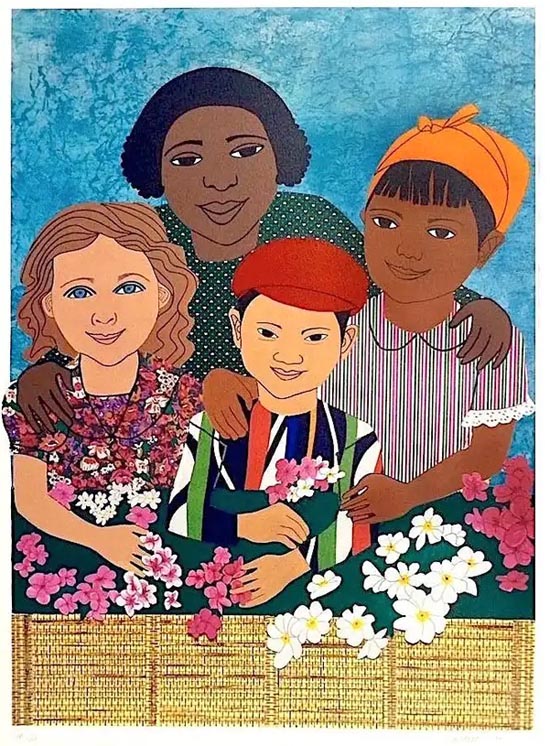

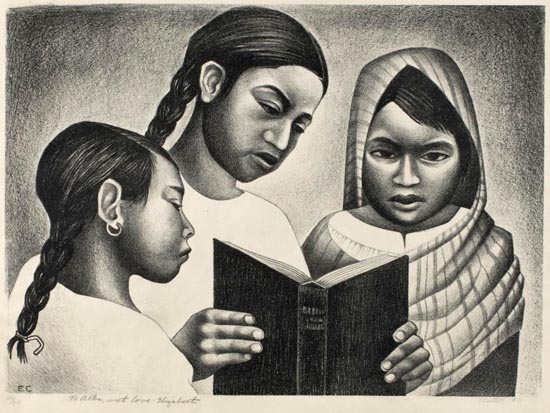

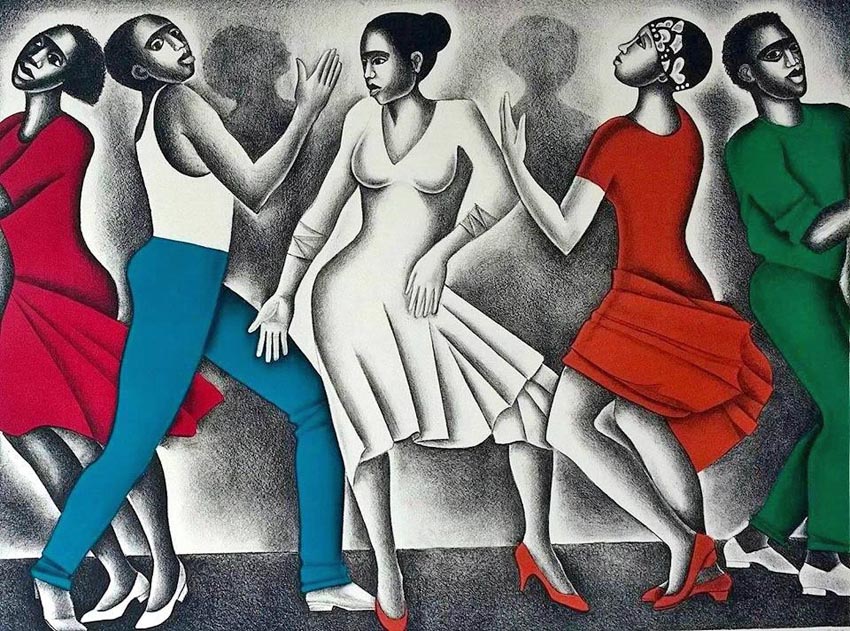

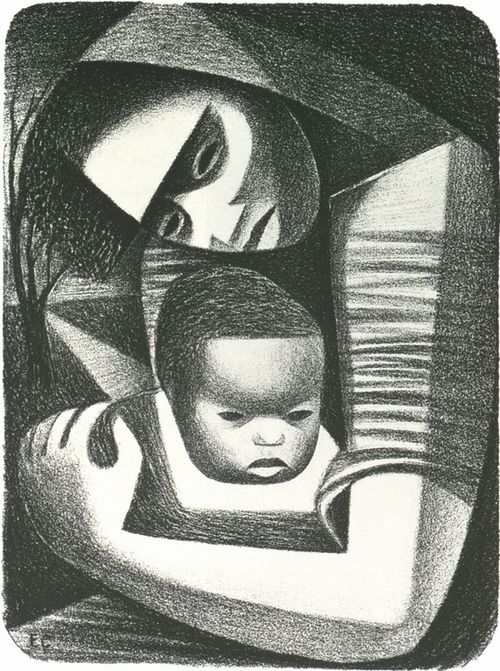

Ms. Catlett had a vision for her work as, “an art for people of all kinds.” Her work includes a huge body of linocut prints on a number of themes: the experience of African American life, American-Mexican life, political struggle and ideology, and social themes.

Catlett held the conviction that art should be inclusive, thoughtful, instructive, and inspirational – she wanted her work to be more than “pretty pictures.” Responding to segregation and the fight for civil rights, Catlett’s depictions of sharecroppers and activists showed the influence of Primitivism and Cubism. The messages embedded in her work about human and civil rights resonate with viewers as strongly today as they did several decades ago.

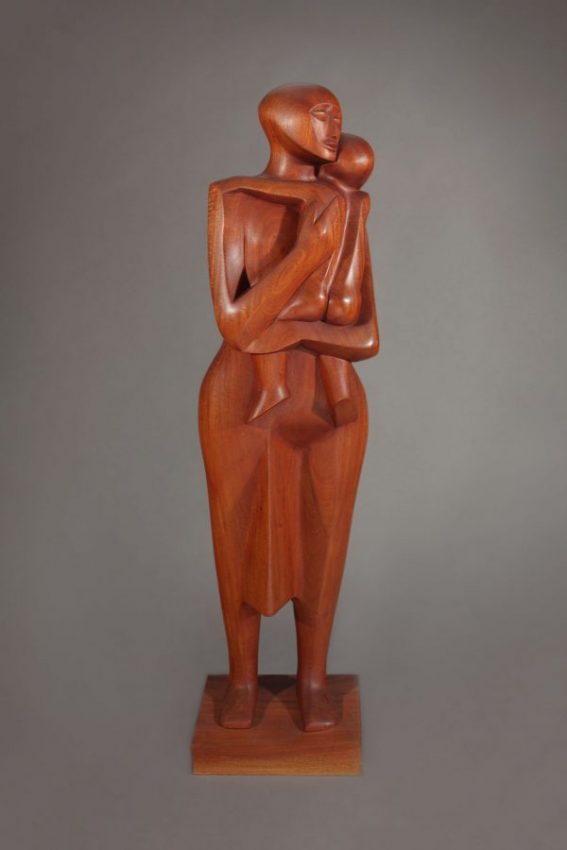

Refused admission to the Carnegie Institute of Technology because of her race, Catlett enrolled at Howard University, where her teachers included artist Loïs Mailou Jones and philosopher Alain Locke. She graduated with honors in 1935 and went on to earn the first MFA in sculpture at the University of Iowa five years later. Her sculpture, “Negro Mother and Child,” won first place at the 1940 Chicago American Negro Exposition.

In 1946, a grant from the Rosenwald Foundation enabled Catlett to move to Mexico City with her husband, printmaker Charles White. Mexico offered her an escape from America’s Jim Crow laws and the opportunity to work at the Taller de Gráfica Popular, a reform-minded printmaking collective with which she shared a commitment to collaboration, accessibility, and affordable art for all. At the Taller, Catlett met the Mexican artist Francisco Mora, whom she married after divorcing White.

In the 1950s, the House Un-American Activities Committee and the U.S. embassy in Mexico investigated the Taller de Gráfica Popular and Catlett specifically for her bold artwork, political activism, and communist affiliations. After being declared an undesirable alien by the State Department she gave up her American citizenship.

Her works have been showcased in numerous solo exhibitions; many are held in the collections of numerous tier-one museums. Hampton University (steward of the preeminent African American fine arts collection) is home to more than 100 works by Catlett.

An article on Elizabeth Catlett will be featured in August 2024.

*Samella S. Lewis, African American Art and Artists (University of California Press, 2003), 134.