DNA – Bloodlines and the Family of Mankind was inspired by the idea of drawing humanity together. In the exhibit, Toni Scott’s personal mitochondrial DNA is shared and complemented with in-depth research on 500 years of her family history, and includes the events that shaped it. The vessel was part of an exhibit at the Arthur M. Sackler Museum of Art and Archaeology in Beijing, China in 2015.

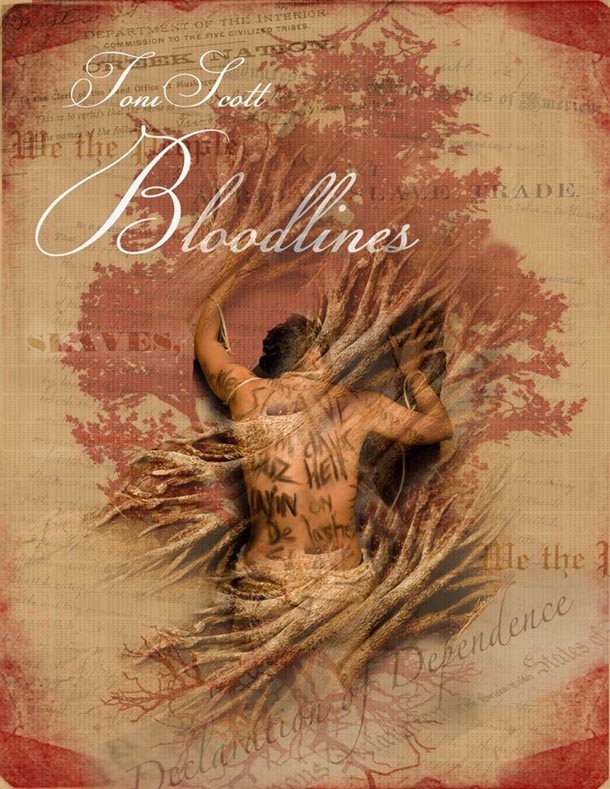

California-based multimedia artist Toni Scott talks about how, in DNA – Bloodlines and the Family of Mankind, she has woven her own personal family history with the universal history of African Americans and Native Americans in a celebration of the human spirit. Expanded here into an overview of the history of African Americans and Native Americans and their relationship to the peoples of Asia and Africa, Scott explores how far-flung, disparate cultures are both joined and severed.

Toni Scott: ‘People don’t understand that what’s in the past is still with us today’

DNA – Bloodlines and the Family of Mankind was inspired by a very personal family investigation into the travails from the continent of Africa, through the grotesque institution of slavery to Georgia, and eventually to Los Angeles, California. Scott was indelibly moved by her family’s legacy of tenacity and survival. In Bloodlines, she reconnects with a span of 302 years of stories, images, and compassion demonstrated by her ancestors.

“The knowledge of my bloodline has become immeasurably important to me. Every iota of information has touched me.”

Through her personal story, the broader truth is that hers is an American story that represents an interconnection of millions of people by race, religions, and regions, as a new American nation was built. Bloodlines is where the past and the present intersect and profundity and meaning are, hopefully coalesced. It is a testimony of the dehumanizing cruelty of institutionalized slavery and post slavery colonialism in America, and the human spirit that would not be broken.

Even today, residual attitudes and behaviors born from the degradation of being enslaved in America haunt and sometimes inhibit the furtherance of our more perfect union. As America becomes an even greater multicultural, multiracial country, it is important to examine the historical foundation that has shaped this great country.

The heart of the exhibition was an approximately 24-foot long, illuminated slave ship suspended from the gallery ceiling, just above the heads of the viewers, constructed from 500 translucent images of both family members and faces taken from archival collections, blue-tinted as if they had been stained by ocean waves. The portraits are an attempt to restore the individuality of the countless, all too often anonymous souls who were forcibly uprooted from their homes, transformed into chattel sentenced to hard labor in the Americas.

Another highlight was a to-scale tipi erected in the courtyard (there is a smaller one in the entrance space), a contested icon that Scott installed to represent the Native American side of her heritage (she is a citizen of the Muscogee Creek Nation). The exterior of the tipi is emblazoned with traditional designs and symbolic colors; the interior inscribed with the names of all the tribes that existed in North America.

Shown with them are more family photographs, illustrating the breadth of Scott and her relatives’ ethnic makeup, and transcriptions of slaves describing their experiences that includes a poignant, rather ghostly aural component in which their voices can be heard.

Additionally, there were enormous banners with figures (often of the artist) emblematic of significant historical moments, written text on two walls that is a lament for an abducted child, genealogical charts tracing Scott’s maternal and paternal lineage, and documentation and images that compare Asians, Africans and Native Americans in a blend of the personal, the ethnographic and sociological, the historical and the poetic, proceeding from the specific to the general.

Ultimately, Bloodlines celebrates not only the will to survive but also the “human spirit”, as Scott said, in all its magnificent diversity. As well, it celebrates our surprising homogeneity, in which only a few degrees of separation stand between us all.

According to Scott, “Learning of my own heritage has inspired me to give life to the “lost images and events” of history, and call attention to the long-forgotten victims of slavery in America, and the genocide of millions of Native Americans, while also sharing the cultural richness of African and Native American people. My artwork further celebrates and shares inspiring stories and history from my tribe, the Muscogee (Creek) Nation, and gives tribute and recognition to all Native American tribes. DNA results of my mitochondrial bloodlines support the exhibition with evidence of my Native American genetic heredity, and its genetic ties to China, while also detailing the Out of Africa migration of all humankind throughout the globe.”

The installation seeks to inspire a broader sensory and narrative experience, in an environment where you, the viewer, are fully immersed. The 24 foot (8 meter) ship represents several concepts: the origin and journey of mankind out of Africa; the journey Scott’s Asian ancestors likely traveled by ship along the coast to the Americas; and the long and horrifying journey millions of Africans experienced as prisoners in large cargo ships specially converted for the purpose of transporting slaves, especially newly purchased African slaves, to the Americas.

The blue color of the faces making up the ship symbolizes the ocean, the blue spirit and sadness experienced by the slaves in transport; it is also used as a psychological tool to balance the horror of the event with a color that helps to promote calm in support of the viewer’s experience.

The images on the ship reflect true-to-life photographs of African American slaves collected from the Library of Congress, which Scott artistically cropped and embellished for this installation. The transparencies are woven together with twine (representing ancestry ties), and are then tied to a frame made of Chinese bamboo.

On the gallery walls surrounding the ship are images of self-portraits digitally composed and set within the context of Scott’s family ancestry, American historical events, and the Native American/Chinese genetic connection. Interspersed in the portraits are maps reflecting man’s journey out of Africa, DNA helix structures, and more.

Visit Toni Scott’s website, www.toniscott.com/exhibitions1, for additional exhibits, photos, and information.